By Dr. Katherine Schrubbe, RDH, BS, MEd, PhD.

Key elements of Bloodborne Pathogens Standard are often overlooked.

For all dental practice settings, OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens (BBP) Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030) provides the fundamentals for a safe workplace, prescribing safeguards to protect workers against health hazards caused by bloodborne pathogens. The Standard places requirements on employers whose workers can be reasonably anticipated to contact blood or other potentially infectious materials (OPIM), such as unfixed human tissues and certain body fluids.1

All of the elements of the BBP Standard are important and work together to provide a comprehensive plan for dental healthcare worker safety. Most dental team members are familiar with several points, such as requirements for an exposure control plan and personal protective equipment (PPE), the opportunity to obtain a hepatitis B vaccination and the implementation of universal precautions.2,3

Some elements of the BBP Standard, however, are often overlooked. Based on personal anecdotal and field observation, the concepts of engineering controls and work practice controls are not always assigned the importance – or the attention – they deserve. Dental healthcare workers not only are exposed to human bloodborne pathogens, but also to toxic chemicals in the workplace. But OSHA makes it clear: Engineering controls, as well as work practice controls, are vital to overall safety.2,4

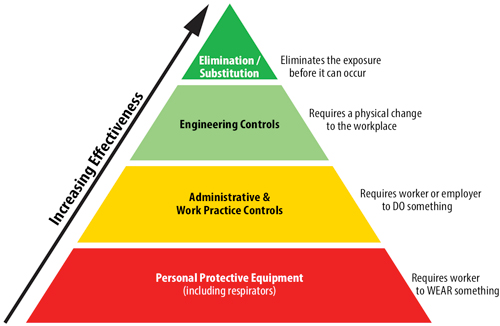

OSHA’s longstanding policy is that engineering and work practice controls must be the primary means used to reduce employee exposure. Wherever possible, elimination or substitution of a hazard is most desirable, followed by engineering controls. Administrative or work practice controls may be appropriate in some cases where engineering controls cannot be implemented, or when different procedures are needed after the implementation of the new engineering controls. Personal protection equipment is the least desirable, but may still be effective.5 The pyramid chart below illustrates least effective to most effective methods for reducing occupational exposure.

With regard to all healthcare, including dentistry, engineering controls refer to controls (e.g., sharps disposal containers, self-sheathing needles and safer medical devices, such as sharps with engineered sharps injury protections and needleless systems) that isolate or remove the bloodborne pathogens hazard from the workplace, according to OSHA. Work practice controls refer to controls that reduce the likelihood of exposure by altering the manner in which a task is performed (e.g., prohibiting recapping of needles by a two-handed technique).3 In other words, it’s product versus process. Engineering controls are products or devices that have been made or manufactured to help reduce the risk of injury; work practice controls are strategies or processes that dental team members should implement to reduce the risk of injury and practice as safely as possible.

Engineering controls

According to C.H. Miller, engineering controls isolate or remove the hazard from the workplace. In dentistry, this means the use of devices that eliminate or reduce chances of exposure to blood and saliva. These include sharps containers, needle safety devices, red-bags, rubber dams, high-volume evacuation, instrument cassettes and mechanical instrument cleaners. The controls used must be examined and maintained or replaced on a scheduled basis.4,6

Although the requirement to utilize engineering controls has been in effect since the 1992 BBP standard, because occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens from accidental sharps injuries in healthcare and other occupational settings continued to be a serious problem, Congress required modification of the BBP standard. As such, the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act was signed into law on November 6, 2000, to ensure that OSHA’s BBP standard set forth in greater detail OSHA’s requirement for employers to identify, evaluate and implement safer medical devices, such as needleless systems and sharps with engineered sharps protections.1,7

The Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act took effect on April 18, 2001, and mandated additional requirements for maintaining a sharps injury log and for involving non-managerial healthcare workers in identifying, evaluating and choosing effective engineering and work practice controls.1,7 In dental practice settings, this is a sound strategy to promote safety and team involvement. As new sharps safety devices become available in the dental marketplace, team members should bring them into their practice and test them out. They should trial the new device for a period of time, ask for feedback from one another, document the safety trial and determine if the device is something that could be implemented to promote a safer workplace.

Work Practice Controls

Miller points out that work practices can be used to reduce the likelihood of exposure by altering the manner in which a task is performed; all procedures must be performed in such a manner as to minimize the spraying and spattering of oral fluids.4,6 Also, work practice controls assist in carrying out tasks in a safe manner to reduce the possibility of a sharps injury. Miller provides the following list of work practice controls, although it is not all-inclusive:

- Flush mucous membranes as soon as feasible if contaminated with infectious materials.

- Recap dental needles by a mechanical means, such as forceps or another cap-holding device, or by using a one-handed “scoop” technique.

- Prohibit the cutting, bending or breaking of contaminated needles prior to disposal.

- Discard contaminated needles and other disposable sharps in proper sharps containers.

- Prohibit the overfilling of sharps containers.

- Place contaminated reusable sharp instruments in containers that are puncture-resistant, leak-proof, colored red or labeled with the biohazard symbol, until properly processed.

- Eliminate hand-to-hand passing of contaminated sharp instruments.

- Prohibit eating, drinking, smoking, applying cosmetics and handling contact lenses in areas where there is occupational exposure, such as the dental operatory or instrument processing areas.

- Eliminate the storage of food and drink in refrigerators and cabinets, on shelves or on countertops where blood or saliva may be present.

- Store, transport or ship blood and saliva, as well as items contaminated with blood or saliva (extracted teeth, tissue, impressions that have not been decontaminated), in containers that are closed, prevent leakage, colored red or labeled with a biohazard symbol.3,4

OSHA’s mission is to assure safe and healthful working conditions for all working men and women by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance.8 When OSHA standards are followed, job-related injuries, illnesses and fatalities decrease dramatically. At times, dental team members may complain that doing so is cumbersome, overwhelming and challenging, but OSHA has made a significant difference in a positive way. Worker deaths in America are down on average, from about 38 worker deaths a day in 1970 to 14 a day in 2017; and worker injuries and illnesses are down – from 10.9 incidents per 100 workers in 1972 to 2.8 per 100 in 2017.9

It is important for all dental healthcare workers to comply with all of the elements of the OSHA standards, and it is imperative that practice owners and management teams are committed to implementing all aspects of the OSHA standards. This is the only way to ensure that dental team members can carry out their duties safely in the practice and that the dental facility is a safe place to work and care for patients.

References

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Quick Reference Guide to the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/bloodbornepathogens/bloodborne_quickref.html. Accessed May 19, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens fact sheet. Available at https://www.osha.gov/OshDoc/data_BloodborneFacts/bbfact01.pdf. Accessed May 19, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_id=10051&p_table=STANDARDS. Accessed May 19, 2019.

- Miller CH, Palenik CJ. Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2013; 247.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Chemical Hazards and Toxic Substances. Available at https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/hazardoustoxicsubstances/control.html. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Miller CH. RDH. Isolate or remove bloodborne pathogen hazards. Available at https://www.rdhmag.com/infection-control/sterilization/article/16405576/isolate-or-remove-bloodborne-pathogen-hazards. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Frequently asked questions. Available at https://www.osha.gov/needlesticks/needlefaq.html. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. About OSHA. Available at https://www.osha.gov/about.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Commonly used statistics. Available at https://www.osha.gov/oshstats/commonstats.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

Editor’s note: Dr. Katherine Schrubbe, RDH, BS, M.Ed, PhD, is an independent compliance consultant with expertise in OSHA, dental infection control, quality assurance and risk management. She is an invited speaker for continuing education and training programs for local and national dental organizations, schools of dentistry and private dental groups. She has held positions in corporate as well as academic dentistry and continues to contribute to the scientific literature. Dr. Schrubbe can be reached at [email protected].