By Dr. Katherine Schrubbe, RDH, BS, MEd, PhD.

Safety protocols must keep pace with advances in dental materials and techniques

In the hustle and bustle of today’s busy dental practices, safety must remain a priority. Compliance to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations form the foundation and best practices of procedures and protocols that drive this safety. Dentistry is a science that requires not only precision hand skills, but also accurate vision; thus, eye protection from all hazards is critical for a long, successful career of caring for patients.

Most providers are keenly aware of the risks of ocular injury and exposure from spray and spatter of patient oral fluids. The OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard states, “when splashes, sprays, splatters or droplets of blood or OPIM pose a hazard to the eyes, nose or mouth, then masks in conjunction with eye protection (such as goggles or glasses with solid side shields) or chin-length face shields must be worn.”1 The CDC concurs, stating, “dental health care personnel should wear protective eyewear with solid side shields or a face shield during procedures likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood of body fluids or the spatter of debris.”2

A new ocular risk

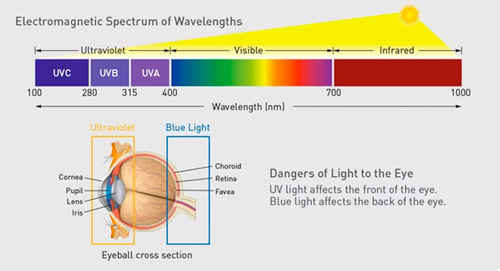

With advances in restorative dentistry and the trend of placing composite restorations rather than amalgam, there is a new ocular risk providers must pay attention to: blue light.3 Light curing units (LCUs) are not only used for curing composite restorations, but also for bonding and tooth whitening, and the lights have become more intensified over time. Most adhesive materials found on the market today contain photoinitiators, material components that require absorption of optical radiation in the wavelength range ∼350-500nm to set. Light emitting diode (LED)-based curing lights are the most used light sources with an emission peak in the blue/blue-green range (430-490 nm).4

Quartz-tungsten-halogen (QTH) light curing units (LCUs) have dominated light curing of dental materials for decades and are now almost entirely replaced by modern LED LCUs. Visible LEDs were invented in the early 1960s. Nevertheless, it was not until the 1990s that LEDs were seriously considered by scientists or manufacturers of commercial LCUs as light sources to photopolymerize dental composites and other dental materials.5

Quartz-tungsten-halogen (QTH) light curing units (LCUs) have dominated light curing of dental materials for decades and are now almost entirely replaced by modern LED LCUs. Visible LEDs were invented in the early 1960s. Nevertheless, it was not until the 1990s that LEDs were seriously considered by scientists or manufacturers of commercial LCUs as light sources to photopolymerize dental composites and other dental materials.5

So, how does blue light affect the eyes of dental team members who use it? Blue light has the shortest wavelengths of all types of visible light (380-495 nm). Accordingly, blue photons have greater energy than photons with longer wavelengths, and high-frequency blue light is sometimes referred to as high-energy visible light.6 Many studies have been done on ocular hazards of LCUs used in dentistry. A recent study by Alasiri et al was published this April, as a systematic review of online PubMed and Google Scholar databases. The objective of the study was to examine the literature and summarize studies that describe the potential ocular hazards posed by different systems of LCUs used in dental clinics to ensure the safety of the operator, patient and auxiliary staff. The results confirmed most of what is now widely known – that blue light radiation can cause moderate-to-severe retinal damage to both dental healthcare workers and patients who are exposed for long periods of time without wearing eye protection. Blue light has a higher energy and can penetrate to the back of the eye at the retina, which is susceptible to damage, risk of burning, enhanced retinal aging and, over time, macular degeneration.6,7,8

Graphic courtesy of Palmero Healthcare

Graphic courtesy of Palmero Healthcare

Along with blue light exposure of LCUs, many practices – especially large groups and DSOs – use electronic patient record systems. The use of computers, phones and other devices with electronic displays are means of additional exposure of eyes to increased amounts of light stimulation. As phototoxicity contributes to the progression of retinitis pigmentosa and age-related macular degeneration, which are major causes of blindness worldwide, the influence of light on the retina is a public health concern.6

How much blue light from LCUs are dentists exposed to? While this differs based on each practice and provider, in a study of Norwegian dentists4, the researchers found they spent on average 57.5% of their working days placing restorations (ranging from 1 to 30 restorations per day). The average length of light curing for one normal layer of composite was 27 seconds. The longest individual mean curing time per day was approximately 100 times higher than that of the lowest. Almost one-third of the dentists used inadequate eye protection against blue light.4

Recommendations for eye safety to blue light

Orange- and/or bronze-colored filters block blue light most effectively. Orange filters cut out more blue light than bronze filters and block blue light wavelengths of anywhere between 385-495nm. Therefore, it is possible to greatly reduce the effects of blue light on the eyes by ensuring that it has to pass through filters, such as functional protective eyewear that contain these colors.6 Where there is not specific guidance related to a worker hazard, the employer can invoke OSHA’s General Duty Clause as a strategy to mandate additional safety measures for employees. The General Duty Clause states, “each employer shall furnish to each of its employees a workplace that is free from recognized hazards that are causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm.”9 Thus, any recognized hazard not covered in a standard, such as the Bloodborne Pathogens, is covered under the General Duty Clause and the employer must implement a feasible and useful method to correct the hazard, such as standard protocols to wear and use special orange filter eyewear to protect dental healthcare team members from potential ocular injury of blue light exposure.

Graphics courtesy of Palmero Healthcare

Graphics courtesy of Palmero Healthcare

Looking away from the light is not recommended; in many cases this behavior causes the curing light operator to move the light away from the restoration area, resulting in decreased light dose to the material, which may compromise restoration quality.4 Currently, the most important recommendations regarding the use of blue light in dentistry are to read the manufacturer instructions for curing devices and to use radiation-filtering protection goggles.6

Protecting clinicians’ eyes from blue light exposure of LCUs is just as important as protecting eyes from patient oral spray and spatter, but not as widely practiced or accepted. Team members must be informed and educated on the hazards of long-term exposure to blue light, and as specific safety eyewear is indicated to reduce the potential of ocular injury from patient oral fluids, blue light filtering eyewear should be utilized to protect the eyes of team members during procedures involving LCUs. Employers and management teams must ensure compliance and keep up with appropriate safety protocols as dental materials and techniques continue to advance.

References

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration; Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_id=10051&p_table=STANDARDS. Accessed September 17, 2019.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health; Personal Protective Equipment.Available at https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/faqs/personal-protective-equipment.html. Accessed September 17, 2019.

- Eklund, SA. (2010). Trends in dental treatment, 1992 to 2007. J. Am. Dent. Assoc., 141(4): 391-399.

- Kopperud,SE., Rukke,HV., Kopperud,HM., Bruzell,E.M. (2017). Light curing procedures – performance, knowledge level and safety awareness among dentists. Journal of Dentistry, 58: 67-73.

- Jandt, KD., Mills, RW. (2013). A brief history of LED photopolymerization. Dental Materials,29 (6): 605-617.

- Yoshino, F., Yoshida, A. (2018). Effects of blue-light irradiation during dental treatment. Japanese Dent Sci Rev, 54 (4):160-168.

- Alasiri, RA., Algarni, HA., Alasiri, Reem A. (2019). Ocular hazards of curing light units used in dental practice – A systematic review. Saudi Dent J, 31(2):173–180.

- Ham, WT, Jr., Ruffalo, JJ, Jr., Mueller, HA., Clark, AM., Moon, ME. (1978). Histologic analysis of photochemical lesions produced in rhesus retina by short-wave-length light. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, 17(10):1029-1035.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. General Duty Clause. Available at https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/oshact/section5-duties. Accessed September 17, 2019.

Editor’s note: Dr. Katherine Schrubbe, RDH, BS, M.Ed, PhD, is an independent compliance consultant with expertise in OSHA, dental infection control, quality assurance and risk management. She is an invited speaker for continuing education and training programs for local and national dental organizations, schools of dentistry and private dental groups. She has held positions in corporate as well as academic dentistry and continues to contribute to the scientific literature. Dr. Schrubbe can be reached at [email protected].